Since the dawning of the United States formalized accreditation system in 1952, accreditation has been a significant driver for education quality management of the modern academic enterprise. This system has been instrumental in establishing a quality culture in higher education. The importance of accreditation is especially visible when it is absent. The nonprofit Accredited Schools Online highlights six risks that students face when enrolling in a school that is not accredited by a recognized accreditor, as determined by the Council for Higher Education Accreditation (CHEA) or the U.S. Department of Education:

- Difficulty finding employment;

- Failing to meet state licensing board requirements for professional licenses;

- Inability to enroll in graduate school;

- Ineligibility to earn federal financial aid;

- Difficulty transferring to another school; and

- Falling prey to institutions that exploit students from minoritized backgrounds and deepen wealth gaps.

Having institutional accreditation is a minimum requirement to avoid these pitfalls and demonstrate quality. Quality being Once a voluntary system of accountability, accreditation is now the first step in ensuring colleges and universities deliver on their mission with ethical, responsible conduct, adequate resources for teaching and learning, systems for evaluation and improvement, and measures of institutional effectiveness. According to the Council for Higher Education Accreditation (CHEA), the outcomes of teaching, learning, research, and service, along with the holistic approach that institutions and programs use to promote learning, practice, and discovery, define academic quality. Essential traits of academic quality include intellectual rigor, honesty, integrity, and the careful alignment of mission and goals with strategies to achieve them. Academic quality also encompasses the expectations institutions or programs have for their students and the dedication, expertise, and effort they invest in fostering student success.

Accreditation: Higher Education’s Answer to Total Quality Management

Clearly, institutional accreditation is the first step in establishing credibility and dedication to quality – but often does not suffice to offer differentiation in a competitive academic market. Higher education institutions across the world, like the US, often seek specialized accreditation as a solution, moving beyond big-picture quality standards to specific outcomes defined by the profession. Program accreditation benefits the public, students, institutions, and the profession itself. For example, specialized accreditation:

- Denotes recognition by peers, both within the institution and the industry.

- Provides a framework for continuous improvement.

- Can allow for better resource allocation within the university to meet standards.

- Boosts recruiting efforts for both faculty and students.

- Helps programs adapt to a changing world.

- Ensures graduates have the competencies needed to succeed in their career.

As such, specialized accreditation has become a preferred practice for demonstrating quality of an academic program, and today, serves as an internationally supported, almost automatic “gold seal of approval” in certain regions of the world for quality in higher education.

Who Is Responsible for Quality?

It is important to note that accreditation itself does not create quality; rather, it is the visible result of an institution’s commitment to its mission and values. Realistically, the ongoing management of accreditation compliance programs can be a stressor for higher education professionals. To succeed and become a natural part of an institution’s operations, accreditation efforts must be met with a culture that embraces ‘quality’ values.

Culture by design is a transformative process that never ends and is evidenced by an institution’s commitment to continuous delivery and integration of quality systems that begin with people, values, and mission alignment. One of the best ways to ensure quality systems run through an entire institution is to avoid silos – quality is everyone’s business.

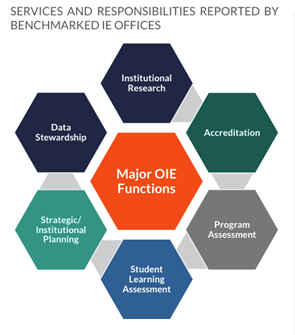

Consider the many areas of quality within a university. Several of the components of quality in higher education are functions of the Office of Institutional Effectiveness (OIE). The 2024 Institutional Effectiveness Office Benchmarking Analysis from Inside Higher Ed by Hanover Research reports six main functions under the OIE umbrella:

Those areas represent vital aspects of quality, but the functions are often dispersed across different divisions. According to the report, universities that integrate their offices of Institutional Research (IR) and Institutional Effectiveness (IE) rather than maintaining them as separate offices enjoy multiple benefits:

- More efficient and effective decision-making

- Higher accountability

- More effective decision making and priority setting

- Better connections of people and systems

- More durable structures and processes

- Full community engagement

This integration can happen either by developing a new office, expanding an existing office, or combining offices or units (an internal merger of research and quality). Hanover recommends that the integrated office include personnel from the office of assessment and other divisions that support accreditation, and that the Integrated Institutional Effectiveness office report to either the Provost or President, with the head of IIE serving as a member of the executive cabinet. (For more information, the report sets forth examples from 11 universities on responsibilities, staffing, and organizational structure of each school’s OIE.)

Creating a Quality Culture

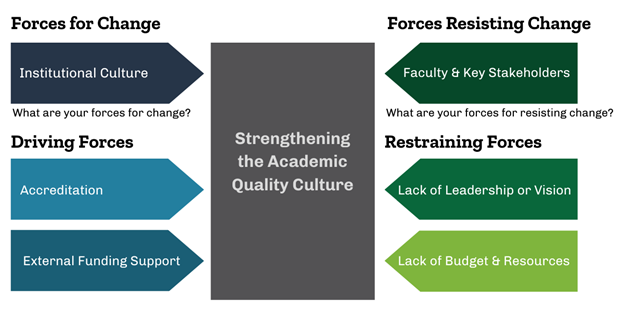

Looking at a university at a macro level, beyond the specific offices devoted to institutional effectiveness, can we determine what drives quality, and what forces work against it? Let us start with the latter. Forces such as budget, lack of process, and omitted mission-vision alignment have become major inhibitors to sustained change and continuous improvement of education programs.

Maintaining accreditation is costly, and the process coupled with managing the strategic direction and creating mission-vision alignment make quality education management a high-stakes proposition for many institutions and academic programs that truly want to achieve organizational and academic excellence. As many institutions are faced with external forces aside from accreditation, the one central force restraining change is culture, specifically the focus on quality in culture. Higher education systems approaching quality efforts often overlook the time investment in building their culture focusing on quality.

Administrators leading academic change and quality improvement efforts must assess the principal drivers for change, duly aligning them to accreditation but more important, the institution’s or academic program’s core value system. Assuming there is an intrinsic motivation linked to quality achievement, the value system harnesses the drivers by which academic quality management leaders can arise and propose new initiatives at any level of the organization.

Creating a culture that recognizes people as the most valuable asset in the academic enterprise, assures administrators, faculty, students, and other key stakeholders can initiate and take ownership of change. In essence, stakeholders, their ideas on and proclivity towards quality are the drivers of sustained continuous improvement in higher education.

Drivers of quality are often attributed to small changes in workflow, stakeholder communications, methods in instruction, and key performance expectations, enabling process efficiencies and effectiveness measures to improve organically over time. Thus, reducing and even eliminating costly forces (change resistance, budgetary constraints, academic bureaucracy, and even shared governance) impeding and slowing down academic quality; further curbing the value system, which seeks to reflect higher commitment and accountability to quality in higher education.

Therefore, institutions and academic programs must share in their belief regarding quality by setting core values that focus on going beyond the status quo and checking the boxes commonly associated with accreditation as the sole driver of quality.

Tools and Practices Supporting Quality Culture

An essential aspect of a quality culture is utilizing assessment tools that provide valuable insights into learner outcomes. Peregrine’s assessment service plays an important role in this process. By offering assessments that measure and evaluate various aspects of academic programs, Peregrine helps institutions ensure they meet accreditation standards and continuously improve their quality. These assessments provide actionable data that administrators and faculty can use to impact teaching and learning methods, ultimately contributing to a robust quality culture within their institutions.

Why are some institutions of higher learning more successful at building, modeling, and transforming culture across their education systems and academic programs? They understand quality in culture is by design. It does not just show up at the proverbial doorstep and ring the bell because they are accredited. It already resides within the institution or academic program and is often revealed in the organization’s ideas, values, and everyday practices and its key stakeholders. Culture, according to Merriam-Webster, is the set of shared attitudes, values, goals, and practices that characterizes an institution or organization; suggesting the administration, faculty, students, community, and its partners must desire a quality culture and make a commitment to organizational excellence. In this regard, we understand institutions and academic programs that demonstrate quality first, make a commitment to an excellence journey, and secondly, the integration of quality as a core value.

What are the inhibitors of quality and how do institutions and academic programs overcome perceived quality barriers? Drivers of quality and forces restraining quality efforts are almost always competing. Therefore, once you make the commitment to quality, you must also commit to the sustainment of continuous improvement efforts that affect quality education management and the internal and external requirements for addressing how quality is measured. Establishing a basis for success ensures clear criteria for outcomes achievement and measurement and evaluation tools for monitoring culture shifts and responding to new drivers and resistors to change as they arise. Balancing these forces requires both strategic surveillance and pragmatic approaches to addressing quality goals. Most of all, it plans for the “people side of change” and assures development, incremental opportunities to grow, and innovation in the academic enterprise overtime to absorb the positive benefits of change.

Leading Academic Quality

In its transformative state, quality improvement creates synergies between faculty, administration, and student beliefs with investment in their development and the maturation of quality processes, technology, and the overall infrastructure. This type of change allows programs to operate at their highest levels. Leaders involved in continuous improvement initiatives must create awareness around the need for quality in academic programs and services. By optimizing their existing capabilities to deliver quality, including managing inefficiencies, such as monitoring process weaknesses and early-stage process deployments, quality leaders (accreditation, assessment, quality assurance managers) can make relatively small changes to yield tremendous results.

In addition, administrators and quality education management professionals should assure the quality objectives are aligned with the vision, mission, and core values. Assuming the planned quality initiatives are well-communicated, the targets and implementation strategies are transparent and authentic to the institution; all academic unit stakeholders should understand their role and how they contribute to quality.Implicit to their design, programs focused on creating a quality culture or strengthening their quality efforts will characteristically approach quality management with these three guiding assumptions:

- Drivers and forces are always at play in the current organizational state, yet the focus on quality is well balanced and managed for successful outcomes.

- The introduction of additional drivers that support improved quality efforts is minimizing or reducing forces that restrain and detract quality. This is approached strategically and in alignment with the current mission, vision, and core values of the institution or academic unit as well as planned horizons.

- Continuous quality improvement is sustained through staged and incremental change initiatives that are routinely measured, monitored, evaluated, and, most importantly, communicated often.

By creating a quality culture, you may not be able to address all the organizational challenges or improve all your quality processes. However, you will facilitate the change that comes with managing continuous improvement and creating synergies between your strategic and operational goals. Thus, consolidating efforts and prioritizing quality in your educational delivery system, whereby small and incremental change can happen without much disruption or threat to the quality system, should be the ultimate goal of your excellence journey.

To read more about the relationship between accreditation, assessment, and quality culture, download the full whitepaper, The Use of Summative Assessment to Improve Quality in Business Administration Programs.